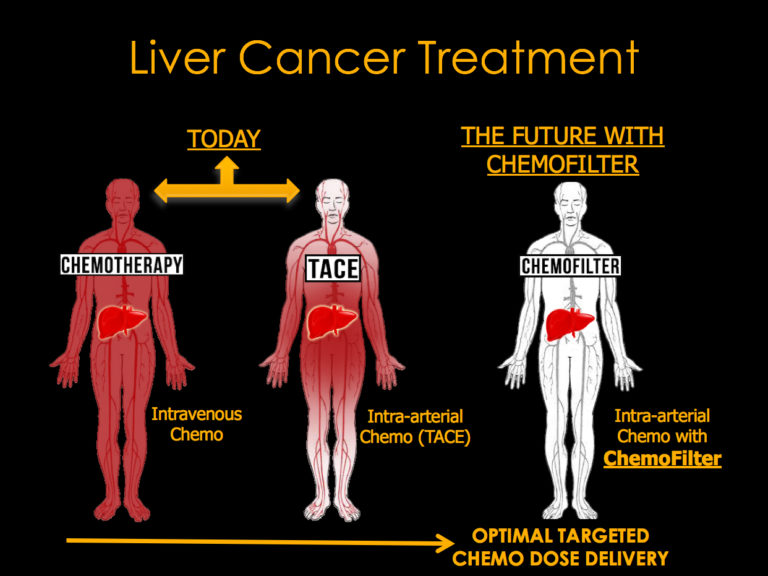

Researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, CLIP 3D printer manufacturer Carbon, and UC San Francisco, have teamed up to leverage 3D printing in an experiment to minimize the side effects of chemotherapy. A so-called “drug sponge,” the ChemoFilter is designed to soak up any excess drugs left over from treatment, preventing them from damaging other healthy tissues in the body.

A much gentler approach to the common intravenous chemo that travels to all parts of the body, the team is seeking preliminary approval from the FDA to trial the filter in patients with liver cancer following successful pre-clinical trials.

Reducing the side effects of chemotherapy

Doxorubicin is a common drug used to treat cancer in the breast, bladder and bone marrow. Though effective at stemming cancerous growth, the drug is toxic to healthy tissue, causing hair loss, bone marrow suppression, vomiting and rashes.

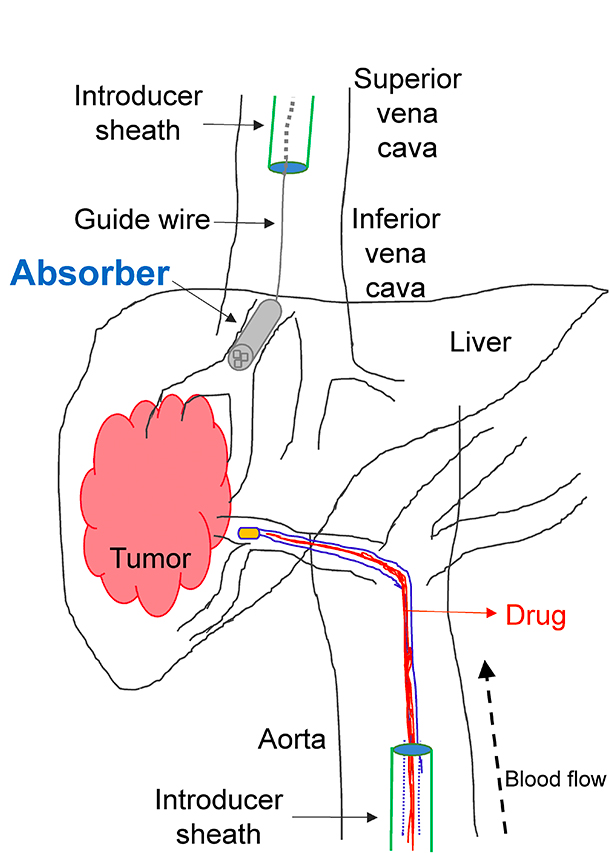

In 2016 Nitash Balsara, a chemical engineer at UC Berkeley, discovered an ionic polymer capable of efficiently absorbing doxorubicin. By combining this discovery with the work of Steven Hetts, an interventional radiologist at UC San Francisco and chief of interventional neuroradiology at the UCSF Mission Bay Hospitals, the two researchers and their respective teams hatched the idea of using the material as a blood filter, or “absorber.”

“An absorber is a standard chemical engineering concept,” explains Balsara, “Absorbers are used in petroleum refining to remove unwanted chemicals such as sulfur,”

“LITERALLY, WE’VE TAKEN THE CONCEPT OUT OF PETROLEUM REFINING AND APPLIED IT TO CHEMOTHERAPY.”

A custom, 3D printed fit

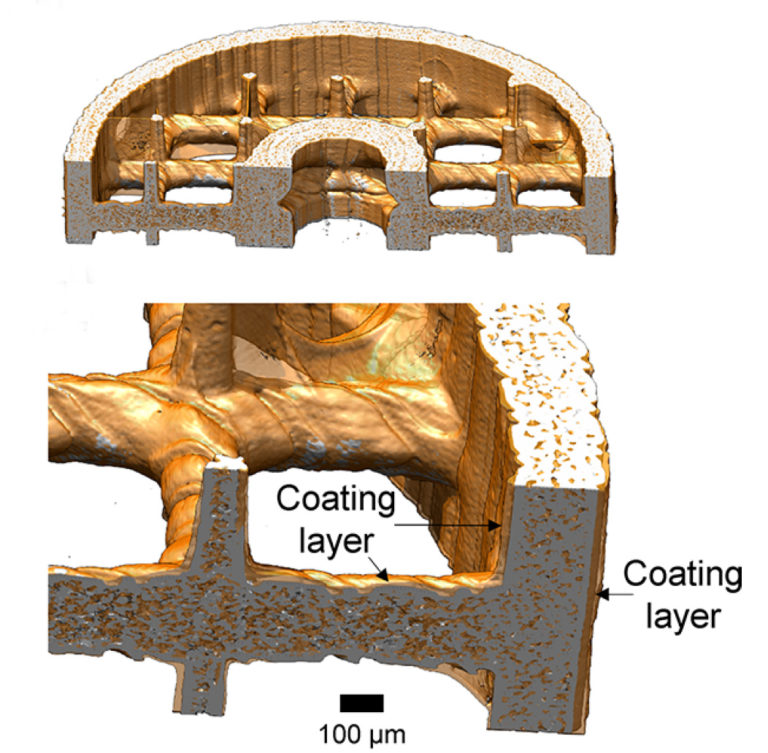

For the idea to work, the team first needed to develop a vehicle that would allow the polymer to fit perfectly inside patient’s veins. This is where 3D printing comes in.

Working with Carbon, Inc. scientists and CEO Joe DeSimone, the UC Berkeley team ensured that the ChemoFilter could be scaled as necessary to make a perfect fit for each individual’s veins.

The finished design is cyclindrical in shape, containing an internal lattice structure. It is 3D printed from one material to start, then coated with the absorbent ionic polymer. Balsara adds, “Fitting the cylinder in the vein is important; if the fit is poor, then the blood with the dissolved drug will flow past the cylinder without interacting with the absorbent.”

Clinical trials in the next 2+ years

Already the 3D printed ChemoFilter has proven effective at filtering the blood in a healthy pig vein. In this test, approximately 64% of doxorubicin injected into the vein was absorbed by the device. The next stage is to transfer the filters to a pig’s liver, however in the next few years the team hopes to be able to test the ChemoFilter in humans.

Hetts says, “Because it is a temporary device, there is a lower bar in terms of approval by the FDA,” and “it is much more realistic to test these in people who have cancer as opposed to continuing to test in young pigs who have otherwise healthy livers.” As such, the team is pursuing conditional approval from the administration to perform the first-in-human studies.

The abstract for “3D Printed Absorber for Capturing Chemotherapy Drugs before They Spread through the Body” is published online in ACS Central Science journal. It is co-authored by Hee Jeung Oh, Mariam S. Aboian, Michael Y. J. Yi, Jacqueline A. Maslyn, Whitney S. Loo, Xi Jiang, Dilworth Y. Parkinson, Mark W. Wilson, Terilyn Moore, Colin R. Yee, Gregory R. Robbins, Florian M. Barth, Joseph M. DeSimone, Steven W. Hetts, and Nitash P. Balsara.

Source: 3dprintingindustry.com