As a first line of defence against the spread of COVID-19 the facemask, a simple covering worn to reduce the spread of infectious agents, has affected the lives of billions across the globe. An estimated 129 billion facemasks are used every month, of which, most are designed for single use. Naturally, this presents a challenge of immense scale to mitigate the impact of disused Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) on our environment. The researchers at University of Bristol developed technology to convert Recycled Facemasks into 3D printer filament.

However, as restrictions are slowly lifted and a sense of normality returns to many campuses across the UK, it’s evident that we’re now facing an altogether different problem; the pervasiveness of PPE litter in our local environment.

Can we turn the waste from PPE into something useful for society something like facemasks ?

Over the years we’ve looked extensively at 3D printing technologies, methods, and materials and after realising that the common blue facemask is not ‘some sort of paper’ but usually a polymer based product with a high percentage of Polypropylene (PP), we started to ponder the possibility of turning it into something we could 3D print with on a desktop printer.

This raised an interesting question for us: Can we turn the waste from PPE into something useful for society, by turning disposable facemasks into a filament for 3D printing?

The following sections of this post document the various stages and findings of interest in going from facemask to filament.

1. The Procurement of Facemasks

2. The Equipment

3. Processing

4. Extruding the Filament

5. Printing with Facemasks

6. Results and Discussion

7. Acknowledgements

1: The Procurement of Facemasks

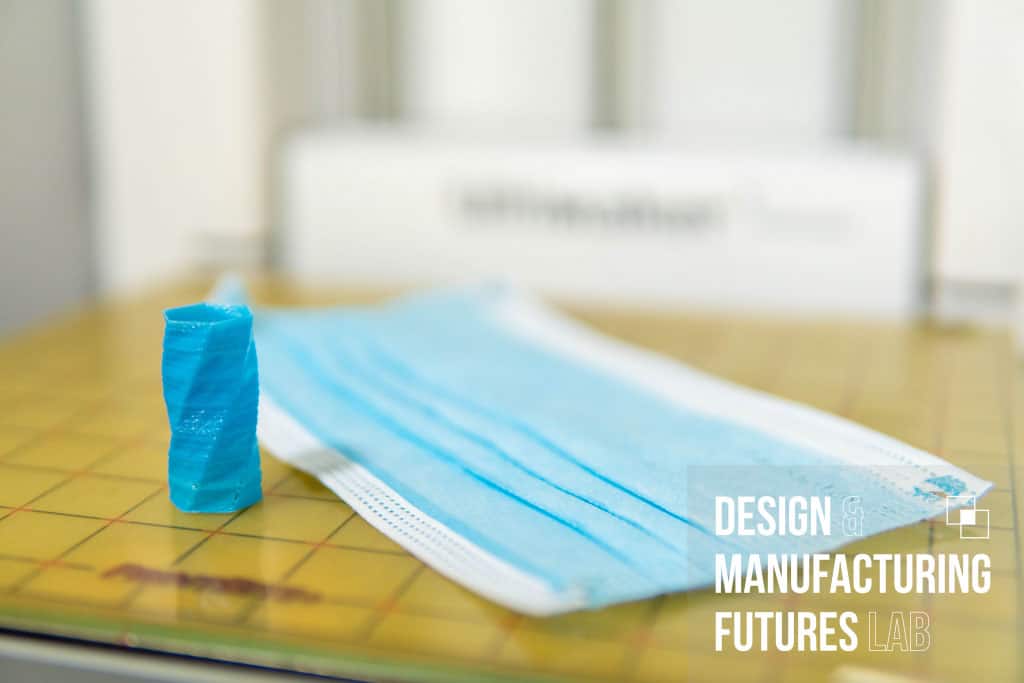

We got in touch with Hardshell UK a leading manufacturer of PPE based in Cardiff who were keen to get involved and very generously supplied 1kg of type IIR Polypropylene facemasks free of charge! The masks (pictured below) are certified surgical products and compliant to EN14683:2019 Type IIR standards.

MASK SPECIFICATIONS

The masks used in this work were manufacturing defects and not suitable for sale. The most common issues being failed ear loop welds, and the occasional missing nose wire.

SPECIFICATIONS

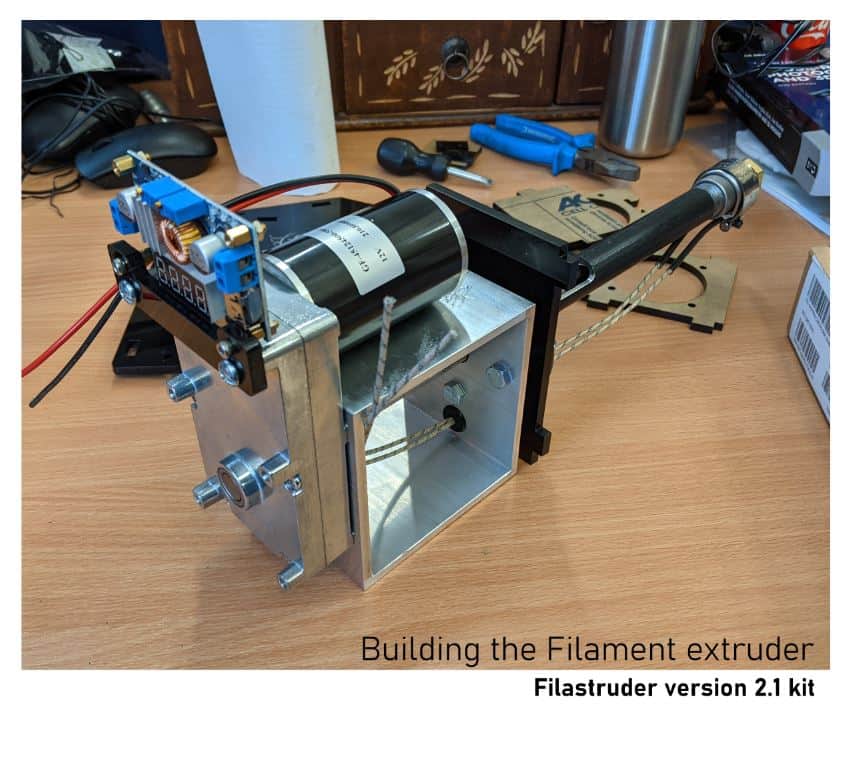

- Motor GF45: 12vDC, 8RPM, 15.6 N-m torque, 1.6A

- Typical Extrusion Rate: 5-8 hours per kg (2.2lbs) (10-36in/min, depending on diameter, material, and temperature)

- Extrusion Temperature: Room temperature to 260C.

- Power: 110-240VAC, 50/60Hz, 60 watts peak, 50 watts average (electrical cost: ~£0.07 per kg extruded)

The image above shows the barebones assembly of the Filastruder kit before adding the controller and wiring. We additionally purchased the complimentary ‘Filawinder’ kit, a device to help spooling the filament and increase the diametral consistency of extruded material. In total both devices cost ~£345 plus shipping from the United States.

A video of the assembled kit is shown in section 4.

3: Processing

We realised through early experimentation that the fibrous composition of masks posed a challenge to any conventional methods of plastic recycling. Other researchers also identify this as the cause of many a ‘clogged machine’. To overcome this issue we introduce a step prior to grinding where the masks are heated and pressed to form a hard sheet; the idea being that by taking the material to its glass transition point we can fuse the Polypropylene fibers to create something with more rigidity. To do this we simply used an iron and non-stick paper.

We realised through early experimentation that the fibrous composition of masks posed a challenge to any conventional methods of plastic recycling. Other researchers also identify this as the cause of many a ‘clogged machine’. To overcome this issue we introduce a step prior to grinding where the masks are heated and pressed to form a hard sheet; the idea being that by taking the material to its glass transition point we can fuse the Polypropylene fibers to create something with more rigidity. To do this we simply used an iron and non-stick paper.

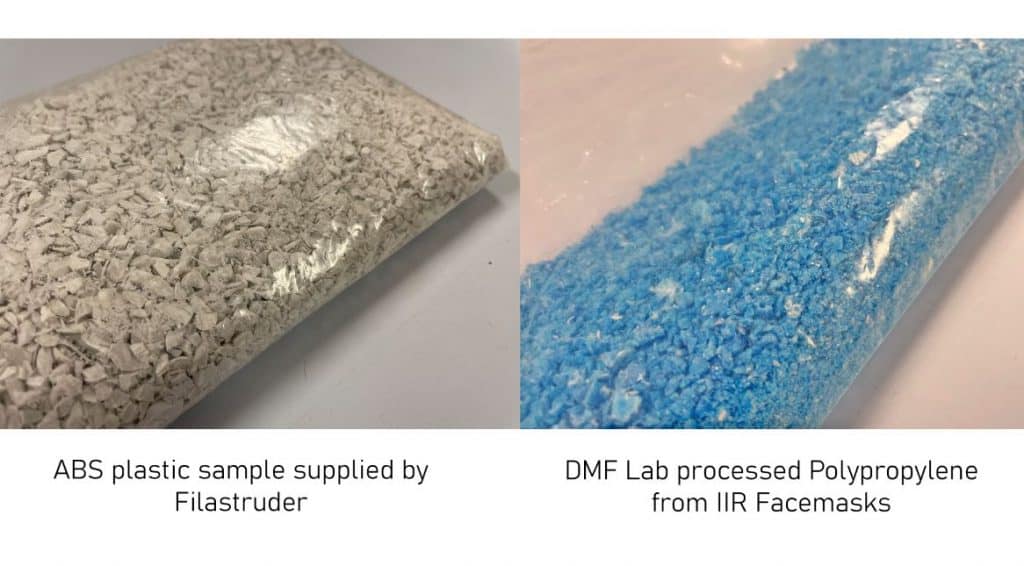

The rigid sheets were then broken up into smaller bits to process through a blender (300W Breville Blend Active) achieving the fine granules of facemask blue PP pictured on the right. For comparison, the sample ABS material supplied by Filastruder is also shown. This process of increasing rigidity improves results from extrusion by reducing pressure instability in the barrel of the filament extruder, and further, prevents fibers from jamming the machine. The blue granules are what we feed into the extruder to produce filament.

The rigid sheets were then broken up into smaller bits to process through a blender (300W Breville Blend Active) achieving the fine granules of facemask blue PP pictured on the right. For comparison, the sample ABS material supplied by Filastruder is also shown. This process of increasing rigidity improves results from extrusion by reducing pressure instability in the barrel of the filament extruder, and further, prevents fibers from jamming the machine. The blue granules are what we feed into the extruder to produce filament.

To address concerns around any contamination of the material produced it should be noted that the masks are heated throughout the process of extrusion to a temperature far beyond that which SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to survive. Another issue to consider is the pre-processing of masks i.e. removing ear loops and metal nose straps. These are fairly easy to remove manually, although could present difficulties in automating the sorting/preparation process. It might be that in the future users are prompted to separate these parts before recycling.

4: Extruding the Filament

5: Printing with Facemask

Polypropylene (PP) is notoriously difficult to 3D print as it doesn’t bond well to common printer build platforms. However, it does bond well to itself, PP. A trick is therefore to print on normal clear tape as this is often also PP. Using this method it was surprisingly straightforward to 3D print with our rudimentary stock of filament on a low-cost, run-of-the-mill machine. It’s very evident that issues currently reside in producing the filament and not in 3D printing with it.

Print Settings

- Printer: Creality Ender 3 Max

- Nozzle temp: 235 C

- Bed temp: 100 C

- Print speed: 40 mm/s (slow)

- Fan speed: 100%

- Retraction: 4mm (Bowden)

- Retraction speed: 30 mm/s

- Flowrate: 350% (account for thinner filament)

We find these settings to have worked well considering the inconsistency in diameter of filament.

Whilst not very widely used as a material in 3D printing, some properties of PP make it an alternative worth exploring. These include the materials durability, and resistance to chemicals and fatigue. Polypropylene is also both food and microwave safe.

In addition to the points above, PP is one of the most common polymers in use. From an environmental standpoint the use of recycled Polypropylene, and polymers in general, poses an opportunity to reduce the consumption of virgin material in rapid prototyping processes such as 3D printing and Injection Moulding.

Roughly a third of a facemask was used to 3D Print this part