Credit: www.3dprint.com

A thumb splint may seem like a simple device, designed to keep an injured thumb stable so that it can heal. But according to a pair of researchers from Deakin University, upper limb splints often do not fit optimally and thus are underused by patients, resulting in a less than optimal recovery. In a paper entitled “Design and additive manufacturing of a patient specific polymer thumb splint concept,” the researchers describe how they used CAD to design a more functional, comfortable and aesthetically pleasing splint, and then used 3D printing to produce it at low cost.

Currently, the researchers point out, the standard practice for making splints is to use plaster of Paris, which can be “highly restrictive and uncomfortable for the patients.” Even with attempts to custom make splints, the rate of non-adherence is relatively high with current techniques and materials. Comfort, appearance, and effects on Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) are cited as reasons why patients do not use the splints.

“With respect to current limitations of current splint devices, insights have revealed a range of factors relating to the non-adherence of wearing an orthoses,” the researchers state. “Factors include difficulties keeping splints clean/dry, poor aesthetical qualities, discomfort due to poorly fitting devices, compromised ability to perform routine tasks and odour related issues. It is believed that the versatility of CAD and AM can be applied to address these issues, realising more ergonomic and aesthetically appealing designs, tailored to the individual’s unique needs and priorities.”

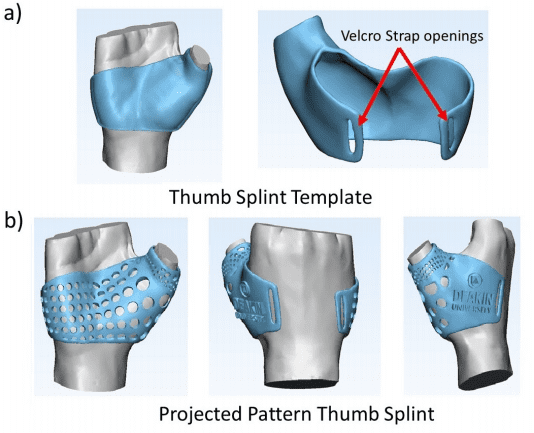

For the study, the researchers scanned a volunteer’s hand using an Artec Spider 3D scanner. They then processed the scanner data using CAD software and created a 3D model of a customized thumb splint. The splint was 3D printed using a Flashforge Creator Pro 3D printer in ABS material. The researchers were challenged to come up with a balance between adequate stiffness to prevent breakage and a device that was as light and thin as possible for comfort. They settled on 3 mm as an ideal thickness for the final design. The splint was also designed to be porous and breathable for additional comfort, and it incorporated openings for a velcro strap.

For comparison purposes, a splint was also made using traditional techniques. This design was not made porous and had adhesive for the velcro strap rather than openings. This alone caused problems because the adhesive pads were prone to losing adhesion and failing after being exposed to moisture. The two splints weighed the same but the 3D printed splint was stiffer.

Once the two splints had been fabricated, the volunteer was asked to wear each one and respond to a series of questions:

- How do you rate the aesthetic qualities of the splint?

- Would you feel happy wearing this device in public?

- How comfortable is the device to wear?

- How stiff would you say the device feels when worn?

- How much mobility of your hand would you say you have remaining to perform everyday tasks?

- How would you rate the device for ease of cleaning your hand and for release of moisture while being worn?

The questions resulted in a rating for each device with a maximum score of 60, with the higher rating being considered optimal. Overall, the 3D printed splint beat the traditional splint by a score of 46 to 26. The 3D printed splint scored higher on each individual question, as well.

The only drawback was that the 3D printed splint took several hours longer to fabricate than the traditional device. The researchers believe that this will be less of an issue as 3D printing technology further develops.