Israeli scientists have 3D printed a heart with human tissue and vessels, marking it a first and a “major medical breakthrough.”

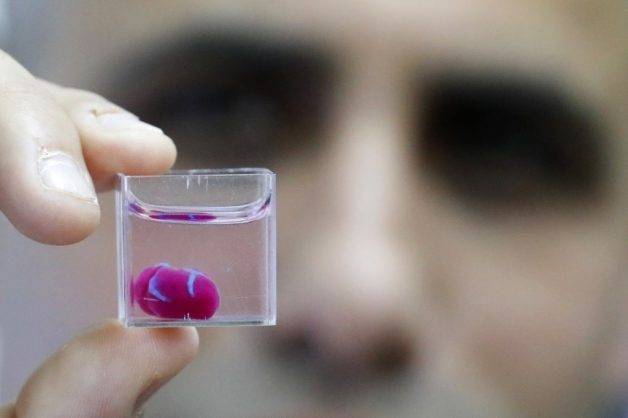

The heart produced by researchers at Tel Aviv University is about the size of a rabbit’s and it marked “the first time anyone anywhere has successfully engineered and printed an entire heart replete with cells, blood vessels, ventricles and chambers,” said Tal Dvir, who led the project.

Researchers say their ‘major medical breakthrough’ will advance possibilities for transplants.

While it remains a far way off, scientists hope one day to be able to produce hearts suitable for transplant into humans as well as patches to regenerate defective hearts.

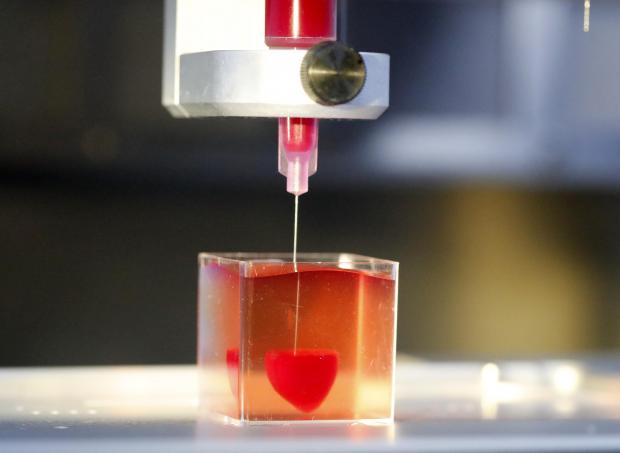

“People have managed to 3D-print the structure of a heart in the past, but not with cells or with blood vessels,” Tal Dvir commented.

But the scientists said many challenges remain before fully working 3D printed hearts will be available for transplant into patients.

The 3D print of a heart about the size of a cherry has been showcased at Tel Aviv University on 15th April, as the researchers announced their findings, published in the journal Advanced Science.

The 3D print of a heart about the size of a cherry has been showcased at Tel Aviv University on 15th April, as the researchers announced their findings, published in the journal Advanced Science.

Researchers must now teach the printed hearts “to behave” like real ones. The cells are currently able to contract, but do not yet have the ability to pump.

Then they plan to transplant them into animal models, hopefully in about a year, said Dvir.

“Maybe, in 10 years, there will be organ printers in the finest hospitals around the world, and these procedures will be conducted routinely,” he said.

But he said hospitals would likely start with simpler organs than hearts.

PRODUCING ‘INK’

In its statement announcing the research, Tel Aviv University called it a “major medical breakthrough”.

Cardiovascular disease is the world’s leading cause of death, according to the World Health Organization, and transplants are currently the only option available for patients in the worst cases.

But the number of donors is limited and many die while waiting.

When they do benefit, they can fall victim to their bodies rejecting the transplant — a problem the researchers are seeking to overcome.

Their research involved taking a biopsy of fatty tissue from patients that was used in the development of the “ink” for the 3D print.

First, patient-specific cardiac patches were created followed by the entire heart, the statement said.

Using the patient’s own tissue was important to eliminate the risk of an implant provoking an immune response and being rejected, Dvir said.

“The biocompatibility of engineered materials is crucial to eliminating the risk of implant rejection, which jeopardises the success of such treatments,” said Dvir.

Challenges that remain include how to expand the cells to have enough tissue to recreate a human-sized heart, he said.

Current 3D printers are also limited by the size of their resolution and another challenge will be figuring out how to print all small blood vessels.

But while the current 3D print was a primitive one and only the size of a rabbit’s heart, “larger human hearts require the same technology,” said Dvir.

3D printing has opened up possibilities in numerous fields, provoking both promise and controversy.

The technology has developed to include 3D prints of everything from homes to guns.