Even without a brain or a nervous system, the Venus flytrap appears to make sophisticated decisions about when to snap shut on potential prey, as well as to open when it has accidentally caught something it can’t eat.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Engineering and Applied Science have taken inspiration from these sorts of systems. Using stimuli-responsive materials and geometric principles, they have designed structures that have “embodied logic.” Through their physical and chemical makeup alone, they are able to determine which of multiple possible responses to make in response to their environment.

Despite having no motors, batteries, circuits or processors of any kind, they can switch between multiple configurations in response to pre-determined environmental cues, such as humidity or oil-based chemicals.

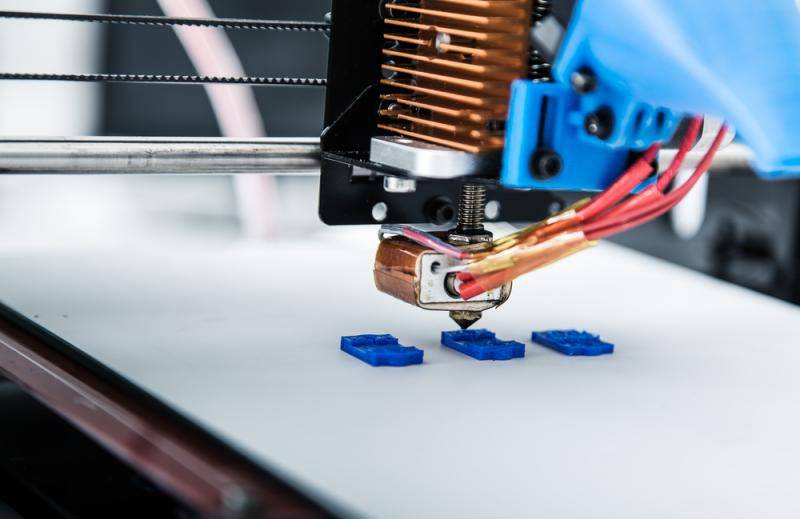

Using multi-material 3D printers, the researchers can make these active structures with nested if/then logic gates, and can control the timing of each gate, allowing for complicated mechanical behaviors in response to simple changes in the environment. For example, by utilizing these principles an aquatic pollution-monitoring device could be designed to open and collect a sample only in the presence of an oil-based chemical and when the temperature is over a certain threshold.

The Penn Engineers published an open access study outlining their approach in the journal Nature Communications.

The study was led by Jordan Raney, assistant professor in Penn Engineering’s Department of Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics, and Yijie Jiang, a postdoctoral researcher in his lab. Lucia Korpas, a graduate student in Raney’s lab, also contributed to the study.

Raney’s lab is interested in structures that are bistable, meaning they can hold one of two configurations indefinitely. It is also interested in responsive materials, which can change their shape under the correct circumstances.

These abilities aren’t intrinsically related to one another, but “embodied logic” draws on both.

“Bistability is determined by geometry, whereas responsiveness comes out of the material’s chemical properties,” Raney says. “Our approach uses multi-material 3D printing to bridge across these separate fields so that we can harness material responsiveness to change our structures’ geometric parameters in just the right ways.”

In previous work, Raney and colleagues had demonstrated how to 3D print bistable lattices of angled silicone beams. When pressed together, the beams stay locked in a buckled configuration, but can be easily pulled back into their expanded form.

This bistable behavior depends almost entirely on the angle of the beams and the ratio between their width and length,” Raney says. “Compressing the lattice stores elastic energy in the material. If we could controllably use the environment to alter the geometry of the beams, the structure would stop being bistable and would necessarily release its stored strain energy. You’d have an actuator that doesn’t need electronics to determine if and when actuation should occur.”

Shape-changing materials are common, but fine-grained control over their transformation is harder to achieve.

“Lots of materials absorb water and expand, for example, but they expand in all directions. That doesn’t help us, because it means the ratio between the beams’ width and length stays the same,” Raney says. “We needed a way to restrict expansion to one direction only.”

The researchers’ solution was to infuse their 3D-printed structures with glass or cellulose fibers, running in parallel to the length of the beams. Like carbon fiber, this inelastic skeleton prevents the beams from elongating, but allows the space between the fibers to expand, increasing the beams’ width.

With this geometric control in place, more sophisticated shape-changing responses can be achieved by altering the material the beams are made of. The researchers made active structures using silicone, which absorbs oil, and hydrogels, which absorb water. Heat- and light-sensitive materials could also be incorporated, and materials responsive to even more specific stimuli could be designed.

Changing the beams’ starting length/width ratio, as well as the concentration of the stiff internal fibers, allows the researchers to produce actuators with different levels of sensitivity. And because the researchers’ 3D-printing technique allows for the use of different materials in the same print, a structure can have multiple shape-changing responses in different areas, or even arranged in a sequence.

“For example,” Jiang says, “we demonstrated sequential logic by designing a box that, after exposure to a suitable solvent, can autonomously open and then close after a predefined time. We also designed an artificial Venus flytrap that can close only if a mechanical load is applied within a designated time interval, and a box that only opens if both oil and water are present.”

Both the chemical and geometric elements of this embodied logic approach are scale-independent, meaning these principles could also be harnessed by structures at microscopic sizes.

“That could be useful for applications in microfluidics,” Raney says. “Rather than using a solid-state sensor and microprocessor that are constantly reading what’s flowing into a microfluidic chip, we could, for example, design a gate that shuts automatically if it detects a certain contaminant.”

Other potential applications could include sensors in remote, harsh environments, such as deserts, mountains, or even other planets. Without a need for batteries or computers, these embodied logic sensors could remain dormant for years without human interaction, only springing into action when presented with the right environmental cue.

Source: University of Pennsylvania