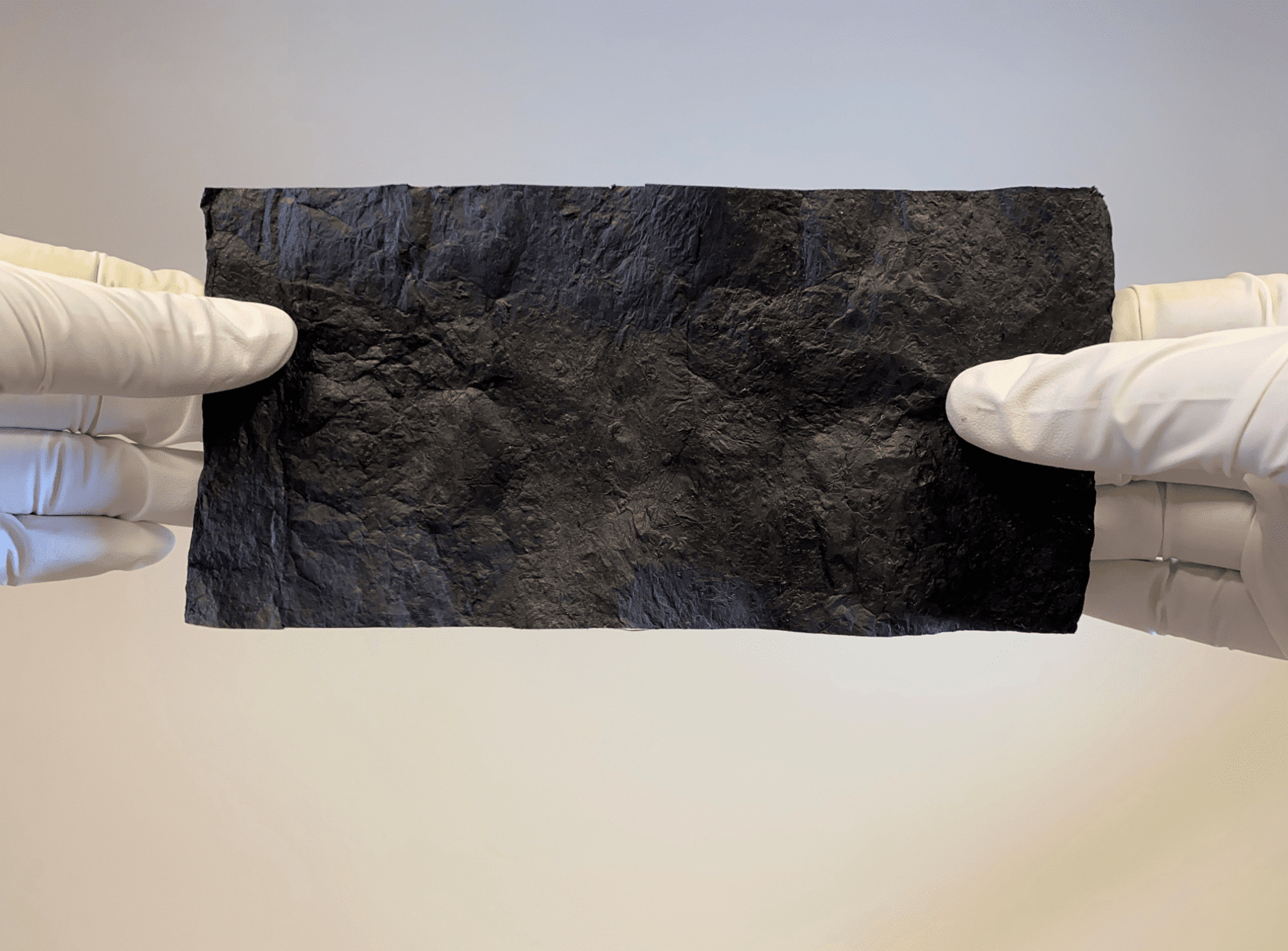

The unsung hero of space exploration, aerospace engineering, and wearable electronics is manufacturable with powder, ink, and a novel 3D printing process. The unsung hero of materials science can clean up chemical spills and weather the temperature swings of outer space. It’s adaptive enough to outfit an aircraft or contour to the human body. And, at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, it’s manufacturable with powder, ink, and 3D printing. Researchers in the Lyding Group discovered an efficient, sustainable method for 3D-printing single-walled carbon nanotube films, a versatile, durable material that can transform how we explore space, engineer aircraft, and wear electronic technology.

More from the News

Made of carbon-based tubes with diameters between 1 and 2 nanometers wide, this small-but-mighty material has been scrutinized by researchers for decades. Gang Wang, the study’s lead author, discovered a novel way to produce them.

“We were inspired by the idea of creating a material that is lightweight, but strong and conductive like metals,” said Wang, a former researcher at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology. “After many attempts, we chose a printing method based on a 3D printer, which produces the film with outstanding properties and high efficiency.”

His method, which is reported in Nano-Micro Letters, is easily scalable and environmentally friendly. Forgoing polymers in favor of a simpler recipe consisting of carbon powder, ink, and a 3D printer enables the team to create carbon nanotube films that are stronger and more durable than existing versions of the material.

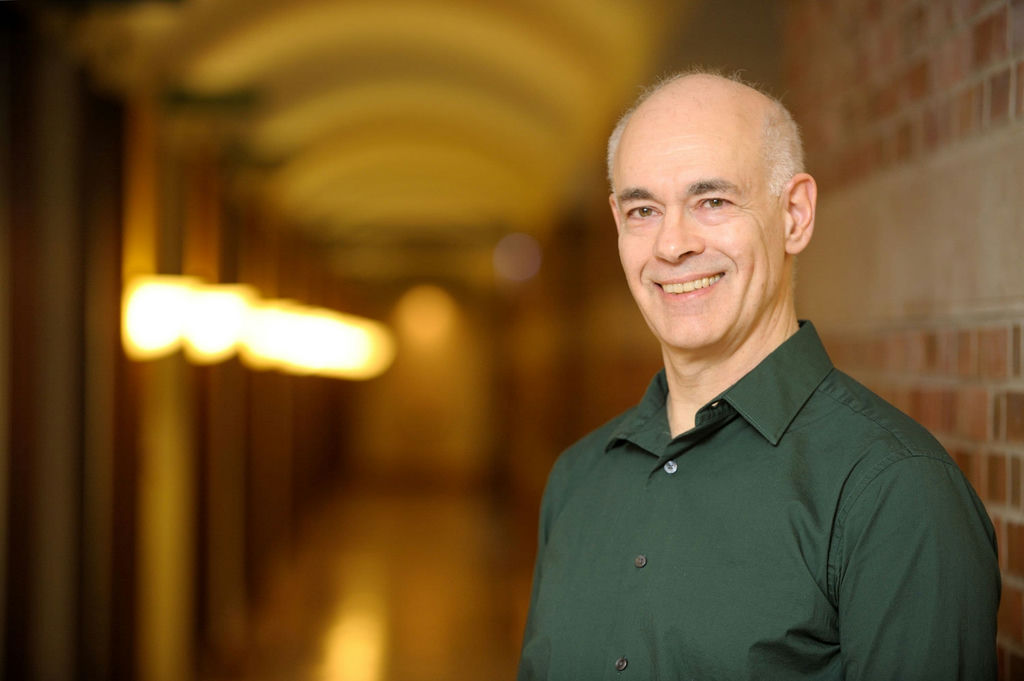

“We’re seeing properties from these carbon nanotubes that are really incredible, said Joseph Lyding, a professor of electrical and computer engineering who has studied and published about the material for years.

Despite weighing only one-fifteenth of what copper weighs, carbon nanotubes are more thermally conductive than their metal counterpart. This helps the materials weather extreme temperature swings not unlike those experienced in space.

“Spacecraft could certainly benefit from the addition of carbon nanotubes. In space, materials are subjected to extreme temperature changes depending on whether they are facing the sun or the cold of deep space. Our films could easily withstand these changes,” Lyding said.

Lying on their sides like logs rolling down a nanoscale river, carbon nanotubes aggregate in large quantities to form films that are centimeters to meters in size, the researchers said.

“Think of the carbon film like a piece of cloth, and the carbon nanotubes are the individual threads in the cloth. The only difference is that we can see the individual threads in our clothing with the naked eye,” Lyding said.

Though approximately 100,000 times narrower than a cloth thread, carbon nanotubes share a function with wool, cotton, and felt — the material’s mechanical flexibility is an ideal characteristic of wearable electronics, refusing to break even after experiencing “deformations like bending, twisting, and kneading,” Wang said.

The films have just as many uses within Earth’s atmosphere as without. Their mechanical flexibility, for example, makes them ideal for vehicles in the air and on land that sustain high levels of jostling and vibration — for example, a rocket launch or moving aircraft. And they’re handy in a crisis:

“Their chemical durability may be useful for prolonging device lifetime or for use in equipment subject to extreme chemical conditions such as inside of chemical reaction vessels or in equipment used for chemical spill cleanup,” Lyding said.

A current researcher at the Beckman Institute, Lyding credits the success of the project to the institute’s world-class facilities and collaborative environment.

“This is an example of something that has its origins in Beckman,” he said of this study. “We used the Microscopy Suite extensively, [for] scanning electron and transmission electron microscopy. We set up the initial 3D printing process in one of the chemical labs in Beckman, and our lab at Beckman is still the home base for this project.”

From the cosmos to the classroom

Given the straightforward method of creating the films with powder, ink, and 3D printing, an immediate application of the technology occurs not in the cosmos, but in a UIUC classroom.

In spring 2022, Lyding incorporated this process into an undergraduate course he developed — Electrical and Computer Engineering 481: Nanotechnology — which contains a unique lab experience led by Dane Sievers that allows students to print their own carbon nanotube structures and measure physical properties like thermal and electrical conductivity.

“Students really like that, especially the hands-on lab. I always have and still do have undergraduate students involved in research,” Lyding said. “It’s an opportunity for students to get involved with something they probably weren’t aware of. Their research is motivating. It brings out a potential some students did not know they had.”

Brendan Wolan, a graduate student studying electrical and computer engineering and a coauthor on this publication, participated in ECE 481 as an undergraduate.

“[It] was my introduction to nanotechnology and was a turning point in my academic and professional career. There is a lot of excitement and energy in the field and this research is at a frontier. Since there are so many unknowns, ECE 481 prioritizes and rewards creativity in the lab.

“The lessons I learned during the class have been invaluable to me as I’ve continued my own research, much of which was born from questions first asked in the 481 classroom,” Wolan said.

Safety and student participation are a priority in Lyding’s lab, ensuring that whether the carbon nanotubes are positioned at the frontier of outer space or a lab space, opportunities for discovery are limitless.

Subscribe to AM Chronicle Newsletter to stay connected: https://bit.ly/3fBZ1mP

Follow us on LinkedIn: https://bit.ly/3IjhrFq

Visit for more interesting content on additive manufacturing: https://amchronicle.com/