For Chinese scientists at Jiangnan University, the shape of things to come rests on a ceramic slurry and 3D printing. The benefits of earlier processes used in 3D printing were often offset by issues of accuracy, speed and economy. Stereolithography, for instance, which employs laser beams to fuse small particles of plastic, metal, glass or ceramic powder into a solid object, generally requires the production of support structures to hold large-scale or oddly shaped structures in place until the components are solidified. This adds time and cost to large projects.

The use of supportive structures—whether in stereolithography or other related approaches—also requires their eventual removal. This introduces potential problems regarding dimensional precision and surface smoothness. Furthermore, removal of support structures could introduce micro-cracks and even structural failure due to added weight stress.

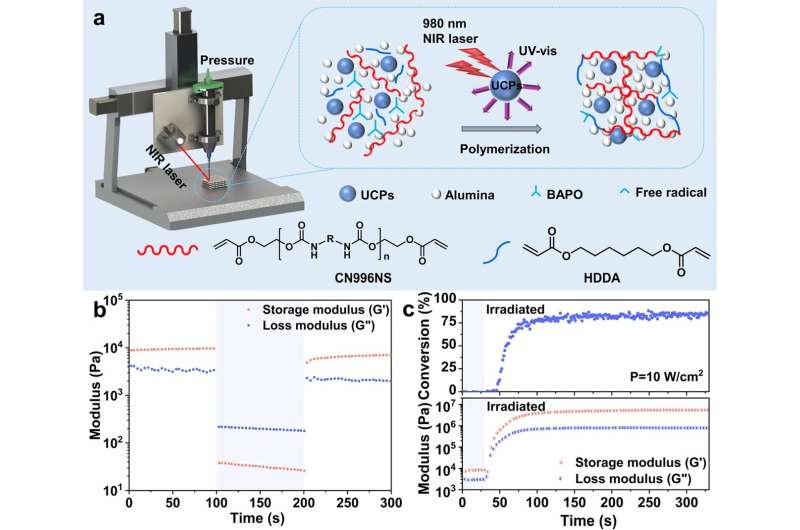

Alternate ceramic production processes that enabled production without the use of support structures used ultraviolet light to harden components. Those processes benefited from greater spatial control during the hardening stage. But that approach was dogged by limitations in the ability of ultraviolet light to penetrate ceramic slurries.

The Jiangnan University scientists found a workaround. They discovered they could construct objects with greater durability and quicker production times by using their ceramic paste with a hardening process based on near-infrared light, rather than ultraviolet light.

“By adjusting the irradiation intensity and printing speed, the ceramic slurry can be cured in-situ during extrusion without the use of supports,” the scientists said in their report published recently by the journal Nature Communications.

“The increasing strength and self-supporting ability of the extruded filaments improves manufacturing precision. More importantly, the flexibility of 3D printing [makes] it easier to print low-angle or even horizontal overhangs without sagging or tilting defects.”

They were able to construct complex objects that were strong enough to maintain their shape and stability in mid-air immediately after extrusion from the printer nozzle.

Comparing results between ultraviolet and near-infrared processes, the scientists found significant differences. When they tested the cure depth (hardening) of the slurry, they found that under ultraviolet light, the curing depth reached 1.02 mm after a little more than two minutes. But with near-infrared light, the curing depth was triple that of ultraviolet light while exposure time was just 3 seconds.

Summing up their results, the scientists said, “By optimizing the ink components and printing parameters (nozzle diameter, extrusion pressure, moving speed, light intensity, etc.), it is possible to obtain objects with higher resolution and unique appearance.”

They expressed confidence that with further studies on the near-infrared printing approach “ceramic geometries produced without support will help generate more innovations and broaden the application of additive manufacturing technologies.”

Subscribe to AM Chronicle Newsletter to stay connected: https://bit.ly/3fBZ1mP

Follow us on LinkedIn: https://bit.ly/3IjhrFq

Visit for more interesting content on additive manufacturing: https://amchronicle.com