Credit: www.3dprintingmedia.network

Tiwanaku, an archaeological site found in Western Bolivia dating back to around 500 AD, is the latest historical site to get the 3D printing treatment. Researchers from UC Berkeley have 3D printed miniature models of the Pre-Columbian site to reconstruct the ruins, which have been ransacked and compromised over the last 500 years.

The site itself spans four square kilometers—making it the largest archaeological site in South America. Evidently, this was too large of a space to 3D print, so the researchers from UC Berkeley focused their efforts on 3D printing and reconstructing a specific architectural structure, namely, the Pumapunku building.

The Pumapunku building, believed to be built around the year 536 AD, was part of a large temple complex in Tiwanaku, which was believed by the Incas to be where the world was created. Over the years, the site and building itself have been of great interest to archaeologists for a number of reasons. The Pumapunku building specifically is considered to be an architectural wonder.

“A major challenge here is that the majority of the stones of Pumapunku are too large to move and that field notes from previous research by others present us with complex and cumbersome data that is difficult to visualize,” explained Dr. Alexei Vranich, the corresponding author of the study published in Heritage Science. “The intent of our project was to translate that data into something that both our hands and our minds could grasp. Printing miniature 3D models of the stones allowed us to quickly handle and refit the blocks to try and recreate the structure.”

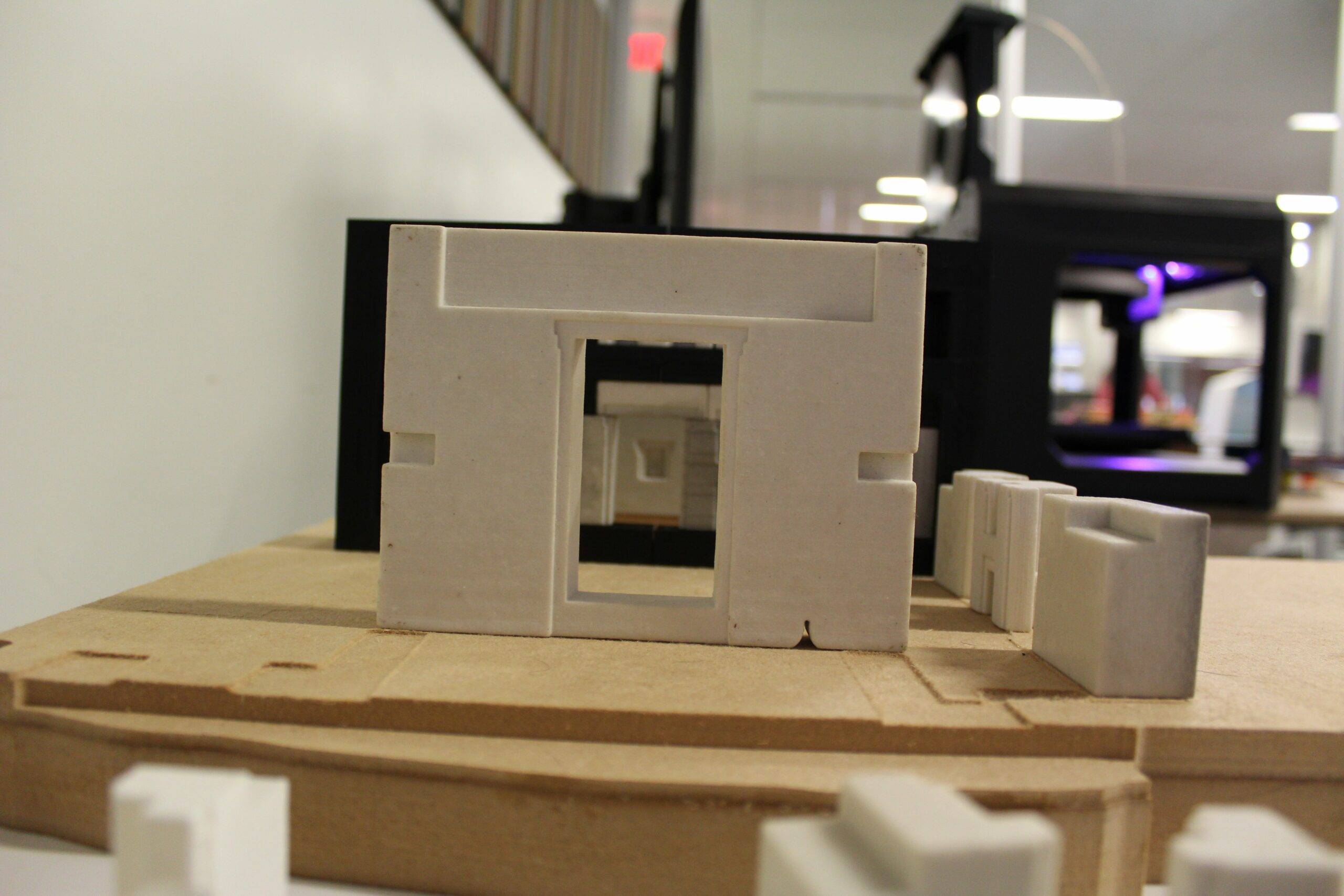

In making the miniature models, the research team 3D printed 140 pieces of andesite, a extrusive rock found in the Andes, and 17 slabs of sandstone, all of which were based on measurements recorded by scholars over the last century and a half of the blocks. With these measurements, the team was able to create 3D models of the blocks and subsequently print them.

Then, not unlike playing with a set of toy blocks, the researchers placed the blocks to reconstruct the site, figuring out how they would have fit together. The physical 3D recreation of the Pumapunku building has given some indication of what the building could have originally looked like and has also given some insight into how the building could have been used.

“One particularly interesting realization was that smashed doorways of different sizes that lay scattered around the site were aligned in a manner that would create a ‘mirror’ effect; the impression of looking into infinity, when, in fact, the viewer was looking into a single room,” said Dr. Vranich. “This may relate to the Incans belief that this is the site where the world was created and could also suggest that the building was used as a ritual space.”

Interestingly, the research team does acknowledge that their method might not be considered the most cutting edge—as it is essentially physically manipulating blocks. But this tactility has offered them benefits, they say.

Dr. Vranich elaborated: “This effort represents a technological step back from recent methods that used computer modelling to recreate structures on screen, but the human brain continues to be more efficient than a computer when it comes to manipulating and visualizing irregular 3D forms. We attempted to capitalize on archaeologists’ learned ability to visualize and mentally rotate irregular objects in space by providing them with 3D printed objects that they could physically manipulate.”

Within the field of archaeology and historical preservation, 3D printing is slowly finding its place. Along with scanning and modeling technologies, additive manufacturing has been used to recreate recently destroyed sites, such as Palmyra in Syria.