Scientists from GE Global Research and the University of California, Berkeley are collaborating to improve production models that will aid in the design and heat treatment of parts. They focused on parts manufactured using additive manufacturing (AM) techniques, in which 3D items are built up, or “printed,” layer by layer, in a recent research. They investigated the creation of internal tension linked with AM processes during neutron tests at the US Department of Energy’s (DOE) Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL). The study’s findings, titled “Monitoring residual strain relaxation and preferred grain orientation of additively fabricated Inconel 625 using in-situ neutron imaging,” were published in Additive Manufacturing.

More about the Study

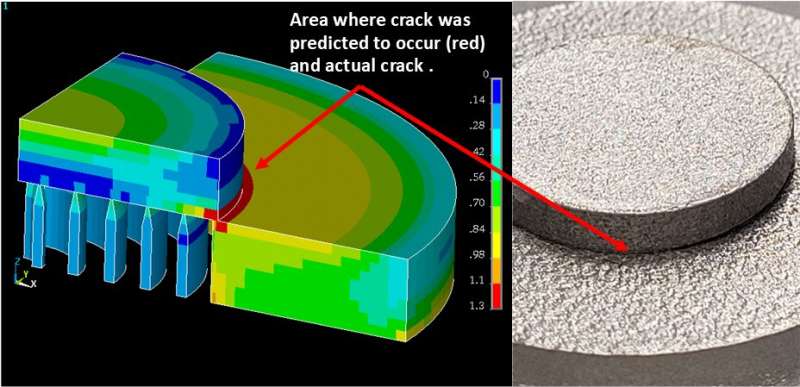

Internal irregularities in made metal components can be caused by the heat, pressure, and force that materials face during manufacturing processes such as forming, casting, and molding. These inconsistencies include distortions and uneven microstructures, often known as “strain,” which can lead to cracking and failure of the components.

Post-build heat treatments, such as annealing, are commonly used to reduce internal strain in produced components. Annealing is the process of heating manufactured components to high temperatures in order to reduce or alleviate internal tension.

The pieces in the study were created utilizing laser-based AM, which uses a laser to melt and deposit a structural material. The molten material—which often begins as a powdered metal or plastic—cools and hardens fast before another layer is put on top of it.

Internal strain can also be caused by laser-based AM because to the fast heating and cooling during the construction process. Although annealing can relieve internal tension, too much heat might create undesirable structural changes in the material.

The researchers observed substantial internal residual strain inside as-built samples of Inconel 625, a typical metal alloy, using neutron diffraction at ORNL’s VULCAN beamline. A complementary approach, neutron imaging, was then employed at ORNL’s SNAP beamline to assess the interior stress of the components in real time. Initial calibration experiments were carried out at the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex’s NOBORU beamline (J-PARC).

“When employing laser AM, the top layer being melted is very hot, whilst the bottom layers have cooled. Internal strains can be created as a result of temperature variations, which can lead to cracking “Ade Makinde, a principle engineer at GE Global Research, agreed. “During the annealing process, neutrons allowed us to see through the furnace walls in real time. We examined where the tension in the material was lowered during heating and at what temperature. It’s a delicate balancing act. We must heat the material to decrease stress, but we must avoid exceedingly high temperatures to avoid undesirable structural changes.”

The information gained is assisting GE in improving its computer modeling of manufacturing processes in order to decrease or eliminate mechanical failures in printed components. For example, the model can demonstrate how altering the design of a part might strengthen it by reducing internal stress during manufacture. It can also show whether adjusting the width of the laser beam or the speed at which it travels might enhance manufacturing quality.

“Neutron imaging at the SNAP beamline allowed the experiment in a way that only a few neutron facilities across the globe can,” said Anton Tremsin, a full research physicist at UC Berkeley. “Yes, X-ray diffraction measurements may track strain relaxation at precise locations. However, neutron imaging allows us to see the full bulk material at the same time, in real time, and with very high spatial resolution. The data will aid us in the development of instruments and data processing methodologies for new non-destructive testing approaches.”

Each 3D printed object was annealed in a vacuum furnace for several hours at either 1,300° F or 1,600° F (700° C or 875° C). As the internal tension was eased, the neutrons readily pierced the vacuum furnace walls and photographed the whole bulk portion. At the lower temperature, stress recovery took 1.0 to 1.5 hours, but at the higher temperature, it took only a few minutes.

“During production, the quantity and distribution of internal strain were related to laser beam speed, laser power, and other factors,” said Ke An, principal instrument scientist for the VULCAN beamline at ORNL’s Spallation Neutron Source (SNS).

“The experimental data is priceless, as is a greater knowledge of how to anneal pieces quickly without compromising structural integrity. That means GE and other industry research partners can now accurately estimate how to enhance their product designs and manufacturing processes.”

“This study demonstrates how industry, academia, and DOE facilities can work together to solve real-world problems,” said Hassina Bilheux, lead imaging beamline scientist at ORNL’s High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR). “ORNL is the only facility in the United States capable of providing complementary diffraction and neutron imaging techniques to the global neutron user community. In addition, we provide high-speed data collecting and analysis skills.”

Bilheux also stated that the VENUS imaging beamline, which is now under development at SNS, will provide users with a wider spectrum of neutron energies to work with. The enhanced SNS linear accelerator’s 2.0-megawatt proton output will also aid user experiments. “VENUS will improve imaging of structural and mechanical behaviors in devices that operate under and are subjected to harsh environments such as heat and pressure. Users will also benefit from the use of novel, pulsed-sourced neutron imaging methods to get a better understanding of a broader range of materials, manufacturing, and production processes.”

“At GE, we are really pleased with the results of these studies and how simple it was to use the neutron facilities at ORNL,” Makinde added. “All of the essential equipment was already installed and calibrated at the beamlines, so we didn’t have to bring our own vacuum furnace, for example. The SNAP beamline’s furnace maintained constant temperatures, and everything was synced to assure reliable data gathering.”

The data is being used by GE scientists to create computer models that can forecast whether and where 3D printed components would shatter. They can then assess how internal stress reduction and design optimization might aid in the prevention of such faults.

Subscribe to AM Chronicle Newsletter to stay connected: https://bit.ly/3fBZ1mP

Follow us on LinkedIn: https://bit.ly/3IjhrFq

Visit for more interesting content on additive manufacturing: https://amchronicle.com/