The last few years have shown us that there are many ways to overcome the constraints of 3D printing and evolve the technology to cater to the demands of end-use part production. Inkbit, a 2017 spinout from the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), uses machine vision and AI to make production-ready, material jetting-based AM systems.

The company is working to bring all of the benefits of 3D printing to a slew of new materials and products that have never been printed before — and it’s aiming to do so at volumes that would radically disrupt production processes in a variety of industries. In other words, Inkbit wants to do for material jetting what Carbon did for stereolithography.

Intelligent printing

While it is not the first company to introduce an element of AI to 3D printing, Inkbit’s CSAIL credentials make its efforts more credible and certainly relevant. Financed by DARPA and Johnson & Johnson among other, the company uses the most technologically advanced polymer AM process – multi-material jetting (or inkjetting) – and pairs it with machine-vision and machine-learning systems. The vision system comprehensively scans each layer of the object as it’s being printed to correct errors in real-time, while the machine-learning system uses that information to predict the warping behavior of materials and make more accurate final products.

This video shows what this process looks like and what it can achieve:

The company says it can print more flexible materials much more accurately than other printers. If an object, including a computer chip or other electronic component, is placed on the print area, the machine can precisely print materials around it. And when an object is complete, the machine keeps a digital replica that can be used for quality assurance.

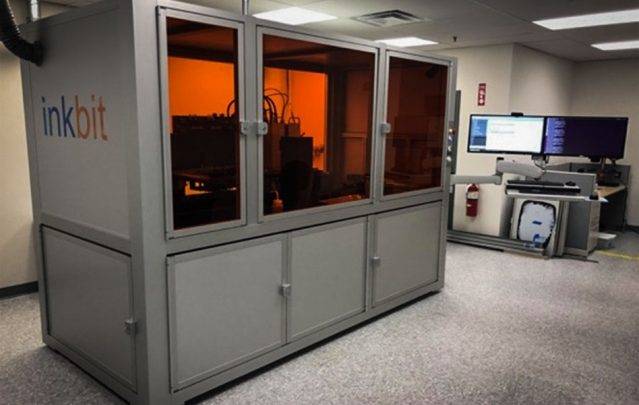

As MIT News reports, Inkbit is still an early-stage company. It currently has one operational production-grade printer. But it will begin selling printed products later this year, starting with a pilot with Johnson & Johnson (a company that is very active in advanced 3D printing projects), before selling its printers next year. If Inkbit can leverage current interest from companies that sell medical devices, consumer products, and automotive components, its machines will be playing a leading production role in a host of multi-billion-dollar markets in the next few years, from dental aligners to industrial tooling and sleep apnea masks.

“Everyone knows the advantages of 3D printing are enormous,” commented Inkbit co-founder and CEO Davide Marini PhD ’03. “But most people are experiencing problems adopting it. The technology just isn’t there yet. Our machine is the first one that can learn the properties of a material and predict its behavior. I believe it will be transformative because it will enable anyone to go from an idea to a usable product extremely quickly. It opens up business opportunities for everyone.”

Dr. Marini was previously the Co-founder and CEO at Firefly BioWorks, an MIT startup that commercialized a novel assay for miRNA detection, based on functional microparticles manufactured by flow lithography. Davide led Firefly from inception to its acquisition by Abcam. He obtained his BS in Industrial Engineering from Politecnico of Milan and his Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering from MIT.

Learning to print

Inkbit’s approach uses e a proprietary high-speed scanning system to generate a topographical map of each layer after deposition. Any discrepancy from the expected geometry is corrected in subsequent layers. These data are also used to train a machine learning algorithm that enables the printer to learn the properties of each material and anticipate their behavior. This ensures parts are built quickly and accurately, every time. Per-layer scanning also allows generating a full 3D reconstruction of each part as-printed, providing a complete digital record of every print, ensuring 100% quality control on every part.

Some of the hardest materials to print today are also the most commonly used in current manufacturing processes. That includes rubber-like materials such as silicone, and high-temperature materials such as epoxy, which are often used for insulating electronics and in a variety of consumer, health, and industrial products.

These materials are usually difficult to print, leading to uneven distribution and print process failures like clogging. They also tend to shrink or round at the edges over time. Inkbit co-founders Wojciech Matusik, Wenshou Wang, and Kiril Vidimče have been working on these problems in Matusik’s Computational Fabrications Group within CSAIL.

Accelerating the future

Inkjet technology allows fast and precise deposition of material at any location in the build. It is also a multi-material technology that allows simultaneous deposition of different materials as well as digital mixing. The Inkbit system deposits up to 4.5 kg of material per hour while building parts accurate to tens of microns. The printer is fitted with 3 build materials plus support and can be expanded to 8. A modular architecture provides the ability to quickly replace, repair, and upgrade components to maximize machine uptime. Automated build plate loading and post-processing means that the entire print process is handled with minimal labor and cost.

In 2016, Inkbit’s four engineers received support from the Deshpande Center to commercialize their idea of joining machine vision with 3D printing. Their task was to make machine vision systems catch up with the machine’s production speed. They started by improving “the eyes” of their machine using an optical coherence tomography (OCT) scanner, which uses long wavelengths of light to see through the surface of materials at 100-micron resolution. Because available OCT scanners were far too slow to scan each layer of a 3D printed part, Inkbit built a custom OCT scanner that is 100 times faster than anything else on the market today.

When a layer is printed and scanned, the company’s proprietary machine-vision and machine-learning systems can now automatically correct any errors in real-time and proactively compensate for the warping and shrinkage behavior of a fickle material. Those processes further expand the range of materials the company is able to print with by removing the rollers and scrapers used by some other printers to ensure precision, which tend to jam when used with difficult-to-print materials.

We still live in a material world

Just like for other key AM production technologies, the true key to end-use parts is material compatibility. INkbit’s contact-less inkjet printing enables the use of new materials that can meet demanding performance requirements. From elastomers stretching over 800% to strong resins capable of withstanding up to 170 °C, they can develop materials meeting a wide variety of customer needs. In addition, inkjet technology’s multi-material capabilities allow for simultaneous printing of soft and hard parts.

Johnson and Johnson, a strategic partner of Inkbit, is in the process of acquiring one of the first printers. The MIT Startup Exchange Accelerator (STEX25) has also been instrumental in exposing Inkbit to leading corporations such as Amgen, Asics, BAE Systems, Bosch, Chanel, Lockheed Martin, Medtronic, Novartis, and others. The future is near.

Source: 3dprintingmedia.network