Researchers from Belgium and The Netherlands offer the details of their recent study ‘Makers in Healthcare: The Role of Occupational Therapists in the Design of DIY Assistive Technology,’ exploring the benefits of 3D printing in clinical practice.

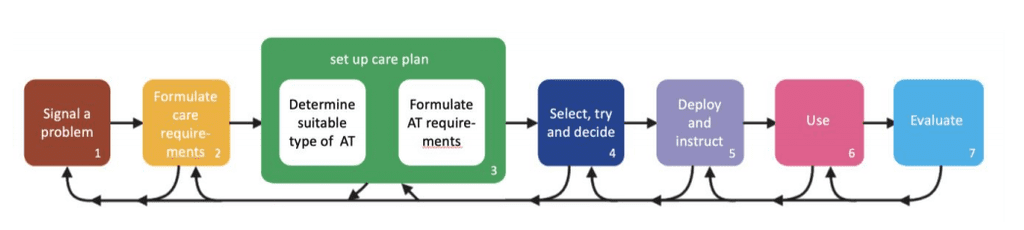

Assistive technology, usually offered to disabled individuals, allows for the completion of tasks that may be otherwise extremely difficult. As 3D printing enters the equation, users are able to take advantage of greater affordability and accessibility to extremely progressive technology, speed in production, and the ability to create customized treatments and devices for patients. With the ability to share designs as open-source, clinicians like occupational therapists (OTs)—and designers around the world working in a wide range of applications—can collaborate in both technique and creation of devices.

Historically, OTs have used conventional techniques like knitting and woodworking to make assistive technology. Because such products require great customization, the researchers note that typical materials used are tape, clay, and cardboard.

“As such, clinicians involved in providing AT to their clients are likely to possess a ‘maker mindset’ and their profession is considered to be highly creative,” state the researchers.

So far, however, not many clinicians are educated in or engaged in 3D printing for assistive devices; in fact, previous research shows that of the AT designs on Thingiverse, less than 13 percent of the makers were actually involved in healthcare. The occupation overall also shows little research by clinicians into DIY AT.

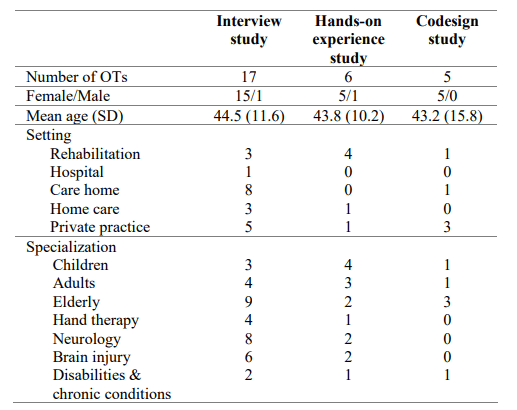

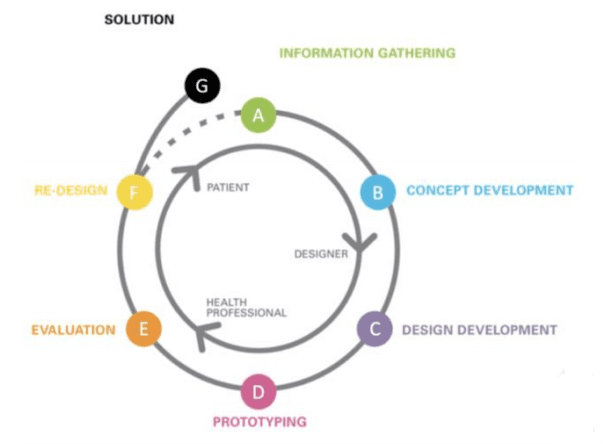

For this study, the researchers observed, interviewed, and worked on several co-design activities with a small group of therapists. It was noted that while they were enthusiastic about 3D printing, they rarely used the technology themselves during the study, and actually thought of the fabrication process as ‘someone else’s job,’ as in that of researchers. Follow-up research also proved the software ‘too complex’ for the occupational therapists to learn at the time, despite potential, and interest. In terms of innovation, research also showed that the OTs were more interested in customizing then creating completely new AT.

While OTs may not see the importance of working as actual AT designers, the researchers explain that such experience is critical ‘as they provide clinical knowledge about clients’ medical needs, daily living needs and socio-cultural needs.’

“So, although it seems agreed upon that the role of clinicians in designing AT is essential, it is not straightforward for clinicians to take up an active role. Several explanations for this have been suggested, mostly related to the fact that existing tools to create DIY AT fall short,” explain the researchers.

Obstacles for clinicians to use existing tools may include:

- Lack of time for learning new methods

- High learning curve

- Difficulty of 3D modeling software

- Lack of understanding regarding potential of the tools

- Challenge in compensating OTs for hours spent prototyping

“These barriers, however, are seldomly based on clinicians’ experience with the act of 3D modeling and printing itself, as in most studies clinicians did not actively engage in modelling and printing,” stated the researchers.

Although this study acted on and contributed to several past research projects also, the authors worked with a total of 17 OTs, observing their attitudes toward the technology, as well as teaching them about 3D modeling software.

Fourteen interviews were performed with the OTs, who were new to 3D printing for the most part. Questions involved topics like safety of AT, quality of AT, the effect on job performance, and OT responsibility.

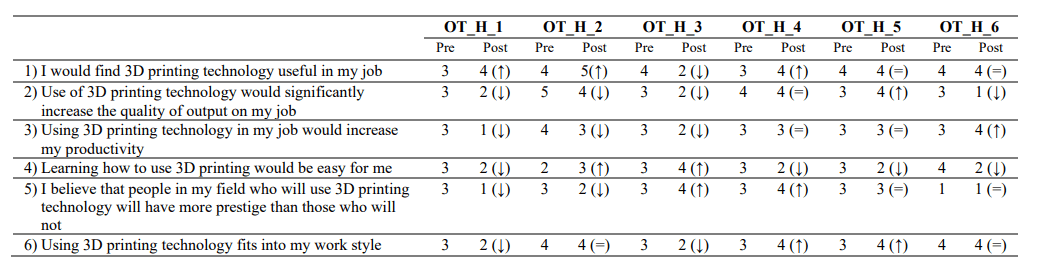

“The OTs in our studies also expressed concerns about 3D printing AT. Most notably, they were worried that creating DIY AT is too time-consuming, as health insurers allow them to spend only very limited time with each client. In addition, they had concerns about the safety of the 3D printing material. Nevertheless, most OTs showed rather positive expectations about the impact that 3D printing could have on their job performance. However, after gaining hands-on experience these positive expectations reduced quite a bit, especially in terms of the impact of 3D printing on job productivity and efficiency, as well as on the quality of OTs output (i.e. the AT they would make for their clients).

“Another commonly reported concern that was also found in our studies, relates to the effort it would take to learn to use 3D printing technology. Because of a lack of relevant (technical) skills, the OTs in our studies anticipated that it would take a lot of time and effort to master 3D printing technology. This is in line with previous research pointing at barriers for implementing 3D printing technology in clinical settings, including software that is difficult to learn for clinicians and time constraints in general.”